Papaya

Papaya (Carica papaya) is a tropical tree-like plant native to Central America. The ripe fruit is soft, juicy, and sweet, like a mango or melon. Commercially, papaya is usually grown in South Florida. With care, however, gardeners throughout Florida can enjoy papayas in their home landscape, too.

Characteristics

Papaya plants are often called “trees” because they can reach over 30 feet tall. While papaya certainly looks like a tree, its care is quite different. In Florida, Carica papaya are short lived, rarely reaching ten years old. In fact, papaya grows as a short-lived perennial in most of the state. Cold weather, high winds, drought, and pests all shorten the plant’s lifespan.

Papaya flowers are unremarkable, growing along the trunk between leaves. The fruits have smooth, thin skin like a mango. Inside, the pulp is orange and the center lined with small black seeds. Papaya fruits ripen on the tree, hanging down against the trunk. The leaves are wide and deeply lobed. They create a small canopy at the top of the trunk, like a palm canopy. Each leaf lasts about six to eight months, falling away as the plant grows taller.

Gardeners hoping to add papaya to their food forest should be aware that papaya comes in three sexes. There are male, female, and bisexual (hermaphroditic) plants. Even within these categories there is some variation based on their environment. Male plants rarely produce fruit and if they do, it’s not of good quality. Female plants produce high-quality fruit but need a male plant nearby for pollination.

Bisexual plants can self-pollinate and produce plenty of fruit on their own. Happily, most of the papaya plants sold in nurseries are female or bisexual. Still, unless the nursery is doing genetic testing, a male plant may be in the mix, too. Check the flowers to determine the sex of your papaya plant; this UF/IFAS publication includes an excellent photo comparing the flowers.

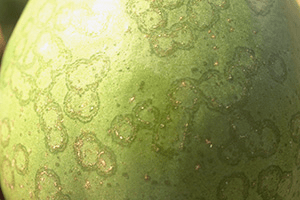

‘Red Lady’, ‘Maradol’, and ‘Tainung No. 1’ are common varieties in Florida. “Solo-type” varieties are also available. These tend to be be more susceptible to papaya ringspot virus. Dwarf-like varieties exist as well, but are hard to find. These smaller plants are much easier to cover or move when the temperatures drop.

Planting and Care

Papaya are not cold tolerant. They grow best in USDA Hardiness Zones 9B through 11. When temperatures stay between 70 and 90 degrees Fahrenheit, papaya thrives. In soil temperatures below 60F root growth slows and declines. Papaya experiences significant damage below 31 degrees and struggle to flower below 59F.

Does this mean dooryard papaya is not an option in the cooler half of Florida? No, but the plants will require significant cold protection. As they reach above ten feet, this becomes more difficult. In response, some gardeners treat papaya as an annual crop. In milder winters, their plants may survive, but gardeners don’t take that for granted. If you live in USDA Hardiness Zone 9A and above, plan on a short lifespan for your papaya. Beginning with the largest papaya plant possible will increase your odds of harvesting fruit. If possible, start plants in containers during winter in a sunny, warm location. Move them out in spring once the temperatures warm up.

Papaya does best when it receives at least six hours of sun. It tolerates sand, loam, and rocky soils and various pH levels. A well-drained spot is best; papaya will not thrive in boggy soils. Where flooding is common, plant papaya in a mound of native soil.

Papaya plants do not tolerate extremes. In addition to temperature highs and lows, conditions such as drought, high winds, or salt spray will reduce your harvest. Papaya prefers frequent, even watering, or it may drop its leaves, flowers, and fruit. Similarly, frequent, small applications of fertilizer are the best option. See Papaya Growing in the Florida Home Landscape for fertilizer recommendations.

We suggest buying a potted papaya plant and installing it in your yard. You can also start papaya from seed. In this case, be aware that you may end up with male and female plants instead of bisexual ones. If you do start from seed, plant at least two near each other to ensure pollination. In colder parts of the state, you can plant papayas in containers. These are easier to move indoors for freeze protection.

Pick papaya fruit when it starts to change from green to yellow. Let it sit on your counter for a few days before eating to finish ripening. Ripe fruits keep for about 4-7 days. You can also harvest it green and cook it as you would a vegetable.

Papaya suffers from several pests and diseases. Nematodes are particularly difficult to manage. If you know your landscape has nematode problems, consider growing papaya in a container. Papaya ringspot virus is another common and deadly papaya problem. If you notice tell-tale ringspots on the fruit, it is time to replace the plant.

For more on adding papaya to your home landscape, please contact your county Extension office.