Starting from Seed

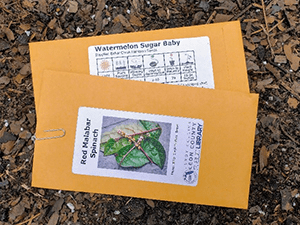

Photo by Tyler Jones, UF/IFAS.

At the beginning of each growing season gardeners are faced with an important choice: sow seeds or use transplants? Many crops, like corn, carrots, and radishes are traditionally sown directly into the soil. Some, like peppers, tomatoes, and cucumber, transplant easily. Others, like Irish and sweet potatoes, are started from plant parts, not seeds. Below is a table listing the transplant ability of a number of common vegetable crops.

One advantage to starting from seed is the wide selection of varieties available through seed catalogs. Another good reason to sow is that it is almost always the more economical option; seeds are cheaper to buy than transplants. Direct sowing does come with a certain amount of uncertainty, though. Over-seed and you’ll be thinning for a long time. Or, if the seeds struggle, you may end up with fewer plants than you hoped.

Transplant Ability of Common Vegetable Crops*

| Easily Survives Transplanting¹ | Sow or Transplant with Care² | Sow seeds or transplants with strong root systems³ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arugula | Chinese cabbage | Lettuce | Carrots | Beans | Peas |

| Beets | Collard | Peppers | Celery | Cantaloupes | Pumpkin |

| Broccoli | Eggplant | Sweet potatoes | Mustard | Corn | Radish |

| Brussels sprouts | Endive/escarole | Strawberries | Potatoes (Irish) | Cucumbers | Squashes |

| Cabbage | Kale | Swiss chard | Spinach | Okra | Turnips |

| Cauliflower | Kohlrabi | Tomatoes | Onions | Watermelon | |

*Transplant ability is the ability of a seedling to be successfully transplanted. 1: easily survives transplanting; 2: survives transplanting with care; 3: only plant seeds or containerized transplants with developed root systems. (Credit: Florida Vegetable Gardening Guide, Table 1)

Below are dos, don’ts and troubleshooting steps for direct sowing in your garden.

DO start with good seed from trusted sources

Success or failure often comes down to the quality of the seed. When possible, buy from a reliable dealer. If the quality of the seed is in doubt, you can check the germination rates by sowing some in a wet paper towel a few weeks before you would sow outdoors.

Seed exchanges allow gardeners to swap seed locally, for free. Many Florida libraries have “seed libraries” on site, stocked with heirloom varieties that do well locally. While the quality of exchanged seeds is a wild card, these seed banks do offer an economical way for gardeners to branch out.

Sometimes you can save seed from your own garden, but proper seed storage makes all the difference. Learn more about seed saving to increase your likelihood of success. Remember, seeds saved from hybrid crops will not be “true” next season.

DON’T guess on timing, variety, depth or spacing

The Florida Vegetable Gardening Guide can take the guesswork out of many of your seed-sowing questions. At the bottom of the document you’ll find a table giving the planting dates, spacing, depth, ease of transplant and more for each of the most common vegetable crops.

One of the most important choices you’ll make as a vegetable gardener is your choice of varieties. Vegetable varieties that perform well elsewhere in the U.S. don’t always have the same success in the Sunshine State. Table 2 of the Florida Vegetable Gardening Guide lists suggested varieties for Florida. The varieties listed in these tables are more resistant to Florida pests and tolerant of adverse conditions than others of the same crop.

Florida is a long state, spanning USDA Hardiness Zones 8a-11a. There is a lot of variation among the 67 counties: temperature, weather, and even soil. If you’ve consulted the Florida Vegetable Gardening Guide and you still have questions, contact your county Extension office. The extension agents and Master Gardener Volunteers there are experts in the local climate and crops.

Sowing the Seed

Planting date, depth, and spacing aside, some guidelines are the same for all seed:

- Sow your seeds in straight rows. This will make it easier to weed and cultivate. Mark off your rows using a string or cord stretched between two stakes. Make furrows (shallow ditches to plant seeds in) along the string.

- Follow the instructions for planting depth and spacing. Seeds planted too deeply may not be able to reach the surface. Seeds planted too shallowly may be washed away by the rain. If your seed packet does not specify depth and spacing, consult the Florida Vegetable Gardening Guide.

- Smaller seeds — Make a furrow as deep as the recommended planting depth. Use a finger or the handle of hoe or rake. You can also broadcast (scatter) the seeds over the soil surface and sprinkle soil on top to cover them.

- Larger seeds — Space larger seeds out evenly and drop them into the furrow by hand. A hoe can help you make a deeper furrow.

- After the seed is dropped or placed in the furrow, use your hoe, rake, or hands to fill the furrow and cover the seed with soil. Leave the ground level or slightly mounded above the seed.

- When in doubt, sow more seed, not less. You can thin plants to the correct spacing after they sprout.

What went wrong?

Here are some of the most common reasons seeds don’t sprout:

- Some seeds are low quality and weak. For better germination (the ability to sprout) and vigor (the ability to grwo stronger), choose tested varieties from reliable sources.

- The seeds may be too old or poorly preserved. Short-lived seeds include onion, corn, okra and parsnip. Beans, carrot, peas and tomato seeds usually last longer. Cucumber, radish, eggplant and squash are long-lived.

- Seeds have hard outer layers called seed coats, but some require help to break open. Certain physiological conditions, like hours in the cold, an overnight soak in water, or abrasion (scarification) may be needed to break dormancy and allow the seeds to sprout. Research your crop before you sow.

- Conditions for germination may be poor. Seeds need air, moisture and warmth in the correct amounts to sprout. Some, like lettuce, even require light to germinate. Read the directions that came with your seeds or research the crop online before planting.

- Disease, insects, birds or other animals may be destroying your seeds. Use cultural pest controls, like netting over garden beds, to deter pests. Additionally, do not apply fertilizer directly to the seeds; this can cause fertilizer burn.

- In rare cases a nearby plant may be keeping the seeds from sprouting. This is called “allelopathy.”

For more answers to your vegetable gardening questions, contact your county Extension office.

Also on Gardening Solutions

- Allelopathy

- Considerations for the New Gardener

- DIY Seed Tape

- Seed Saving

- Seed Sources

- Vegetable Gardening in Florida Series