The Social Structure of a Honey Bee Hive

Honey bees play an important role as pollinators and producers of the sweet substance we like to enjoy with tea or biscuits. But in order to be successful, they must be part of a well-functioning community of bees working together for a common goal. These small creatures coexist in cohesive units with a unique social structure.

Honey bees (Apis mellifera) are eusocial insects, meaning they live in a highly structured social system that governs their lifestyle. They have a “reproductive division of labor” in which there are bees with specific roles in the hive. There is typically one queen (reproductive female), workers (non-reproductive females) and drones (males) in a colony. They also have cooperative brood care in which worker bees care for the queen’s offspring. Queen bees can live several years alongside their offspring; this is called overlapping generations. Other eusocial insects include wasps, ants and termites.

Honey Bee Caste System

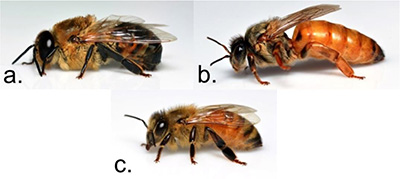

The three “castes” of honey bees (queen, workers and drones) help maintain order in the hive and ensure all tasks get accomplished. The matron of the colony is the queen bee. She is larger than the other bees with a longer and plumper abdomen. The queen’s main responsibility is to mate with drones to produce offspring for the colony. She mainly mates with drones from other colonies, which increases genetic diversity and keeps the hive healthy.

Credit, Mike Bentley, UF/IFAS

The drones, on the other hand, are all males and can be distinguished from the females by their barrel-shaped thorax and eyes that touch at the top of their head. The main role of a drone is to attempt to mate with a queen from a different colony.

In general, worker bees are non-reproductive females that care for the young, forage for resources and defend the hive. They are the most abundant in a colony, with more workers than drones and queens. They specialize in collecting nectar, pollen, water and tree resin. As they age, they progress to a different colony task instead of sticking to one. This is called temporal (or age) polyethism.

Age-related tasks

Worker bees are best suited for different tasks depending on their age. Young workers tend to the immature honey bees (brood) in the central area of the hive. They will feed the queen and young bees and clean the brood cells. As they get older, the worker bees begin to move toward the entrance of the hive, and eventually become foragers. An important role of foraging workers is to build the comb, hexagonal cells made of beeswax where the brood is raised and honey and pollen are stored. The worker bees then begin collecting and storing water, tree resin, nectar and pollen. In the next stage they turn the nectar into honey. The oldest worker bees guard and maintain the hive which includes removing dead bees, as well as forage.

The Hive as a Superorganism

While honey bees are individual insects, their synchronized activities and socialized nature can be interpreted by scientists as a “superorganism.” Each individual within the colony works with its counterparts to accomplish a shared task. This is similar to cells in an animal working together to produce a specific result.

One such shared task is temperature control. Honey bees are constantly regulating the temperature of the hive to be at 93 degrees Fahrenheit. They accomplish this by fanning air over foraged water droplets to cool it down or vibrating their wings around the brood nest to warm the air up. This is similar to the internal workings of a warm-blooded animal, whose blood vessels and organs work to regulate its body temperature.

Honey bees also regulate respiration in the hive. Apis mellifera in the United States usually nest in enclosed cavities where there is very little air exchange. Therefore, it’s up to worker bees to fan air in to and out of the hive entrance, much like the lungs of an animal.

Beehive colonies also demonstrate their superorganism activities with reproduction. Sometimes, an entire colony can be born when swarming takes place. When a queen produces daughter queens, she leaves the hive with as many as two-thirds of the workers to start a new colony. Thus, a new superorganism is born.

Honey bees are fascinating in their social organization and uniquely delegated tasks. Understanding how a hive functions can help us maintain healthy populations and ensure continued pollination of food crops and other plants nationwide. For more information about honey bees and gardening, contact your county Extension office.